Vintage Flute Shop

Articles

“Wood Flutes of the Three Hayneses”

(Top to bottom: J.C. Haynes #317, George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes #2829)

The story of the three Hayneses has been told by Susan Berdahl in her 1986 thesis The First Hundred Years Of The Boehm Flute In The United States, 1845-1945: A Biographical Dictionary Of American Boehm Flutemakers. A short summary is as follows: George and William S. Haynes were brothers and self-taught flutemakers from East Providence, RI. John C. Haynes was neither a flutemaker nor related to them. Wm. S. Haynes worked for J. C. Haynes & Company from 1894 to 1899 before establishing his own flute company, the Wm. S. Haynes Company. More of an inventor than a flutemaker, George Haynes produced a very limited number of flutes under his own name. In 1920, he sold his name and tooling to Selmer in an unhappy venture. The flutes bearing both his name and the word ‘Master’ were products of Selmer. George Haynes collaborated with his brother in some capacity between 1921 and 1930.

Here, I will take a close look at their wood flutes. Their importance then and forgotten beauty now provide much inspiration for this article.

(J.C. Haynes Logo)

BAY STATE (curved)/(line with circle in mid-point)/J.C. HAYNES & CO./BOSTON, MASS./U.S.A./317/L.P.

J.C. Haynes #317 was likely made around 1897 when Wm. S. Haynes was working as the foreman. He oversaw all flute production and made around five hundred instruments including one gold flute. These flutes were all made in-house, unlike some of the imports that the J.C. Haynes & Company also sold under the same trade name “Bay State”.

(Logos of George Haynes,

New York, from around 1912)

GEORGE W. HAYNES/NEW YORK

The wood George Haynes flute has no serial number. The New York location on the flute suggests that it was probably made around 1912. George Haynes returned to New York from Los Angeles in 1905. He also kept a workshop in East Providence where this flute was made. Besides inventing the drawn tone hole technique, George also perfected the forged cup, arm and tail as a single unit, the use of screws instead of pins, and steel bearings inside the tubing of the silver mechanism. All of these inventions were applied to this flute. A similar flute is at the Dayton Miller Collection. In hindsight, George’s early training as a jeweler and, in particular, a toolmaker, led him directly to flutemaking and his many innovations.

(Wm. S. Haynes Logo)

THE HAYNES FLUTE (curved)/MFD. BY/WM. S. HAYNES/BOSTON, MASS./U.S.A./2829

Wm. S. Haynes #2829 was made in 1914, one year after Verne Q. Powell was hired to produce silver flutes. During the first quarter of the 20th century, Wm. S. Haynes Company achieved considerable success making wooden flutes, producing around 1,600 instruments over a 21-year period. Production ceased abruptly around 1921, driven by the shift among flute players towards silver flutes. The company’s decision to hire Powell was a wise one, and his departure in 1927 was a significant loss.

(Top to bottom: J.C.

Haynes, George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes)

(Top to bottom: J.C. Haynes,

George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes)

These wood Haynes flutes look very similar to each other at first glance. Their differences are hidden in the details. They share their basic specifications: grenadilla wood body, C-foot, silver plateau keys with adjustment screws, Bb shake or B/C shake, offset G keys, closed G# key and two lugs on the right hand. Two of the flutes have double rollers to operate low C# and C, the George Haynes flutes uses a single roller and a spatula.

The following chart shows additional specifications and measurements:

|

|

J.C. Haynes |

George Haynes |

Wm. S. Haynes |

|

Pitch |

440 |

438 |

438 |

|

Mainline tone hole |

0.500” |

0.525” |

0.520” |

|

Footjoint tone hole |

0.550” |

0.525” |

0.520” |

|

Regular shake |

B/C |

Bb |

B/C |

|

G/A shake |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

One-piece rib |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Pinned footjoint |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Briccialdi thumb |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Embouchure size |

10.4x11.9 mm |

11.2x12.0 mm |

10.2x11.7 mm |

|

Front angle of emb. |

7° |

0° |

5° |

|

Weight |

491 grams |

501 grams |

487 grams |

|

Outside diameter (OD) |

1.045” |

1.025” |

1.040” |

|

OD at the embouchure |

1.045” |

1.055” |

1.044” |

I will discuss each of these points to understand the motivations behind each maker’s choices.

(Cocuswood J.C. Haynes #1,

silver Boehm and Mendler, courtesy of Robbie Lee)

One of the earliest examples of Haynes’s work that I was privileged to examine was J.C. Haynes #1. Made in 1894, it is a cocuswood flute with sterling mechanism, C-foot, plateau cups, closed G#, B/C trill, pitched at A=446Hz, a close copy of Boehm & Mendler flutes.

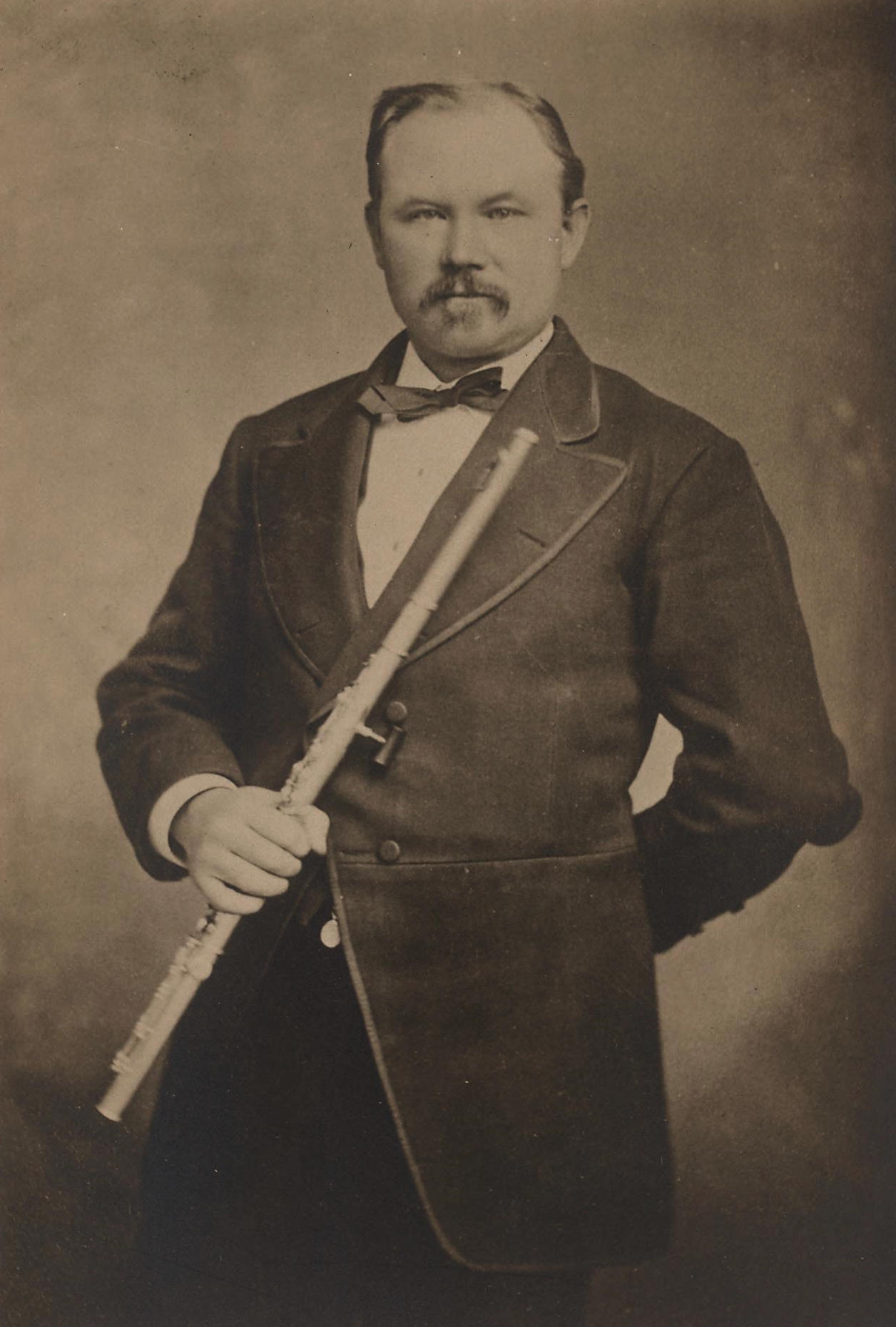

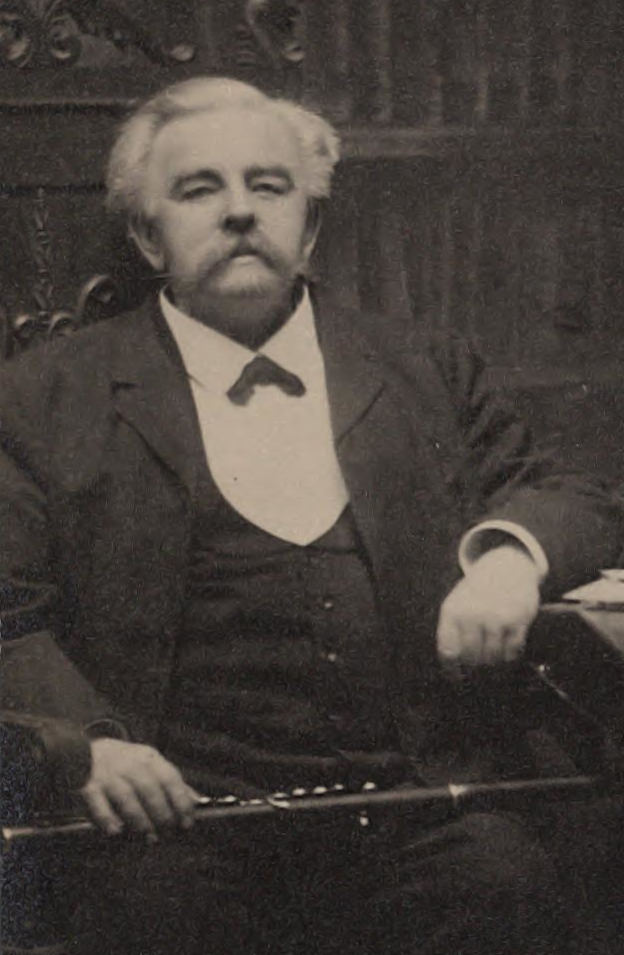

(Photos of Heindl and Wehner

from the Dayton Miller Collection)

Through his association with Edward M. Heindl (1837-1896), who was a student of Theobald Boehm and principal flute of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, it is no surprise that Haynes chose not to copy the flutes of his American predecessors: Badger, Berteling, Meinell, and Ronnberg. He was also influenced by Carl Wehner (1838-1912), another student of Boehm and principal flutist of the New York Philharmonic. Heindl played on a Boehm silver flute while Wehner’s choice was wood. These two men and their Boehm flutes helped sow the seed that blossomed into a century-old Boston flutemaking tradition that is still going strong today.

J.C. Haynes #1 has excellent intonation, the scale feels very similar to that of the early high-pitched Godfroy and Louis Lot flutes. The tone is rich, warm, and woody. The embouchure cut follows Boehm’s dimensions and approximates a square with rounded corners. The workmanship is superb since Haynes was already an accomplished silversmith before becoming a flutemaker. The piece of cocuswood used on this flute is flawless. High quality cocuswood was not readily available in Boston, but it was abundant in London, specifically in Rudall Carte’s stock room. It could have been sourced from England with the help of Wm. R. Gibbs, sole agent for the Rudall Carte flutes of London. He and Paul Fox of the Boston Symphony Orchestra were credited as the first two and only customers of J.C. Haynes & Company’s flute division in 1894. Cocuswood was so rare in America that only six of the 1,600 Wm. S. Haynes wood flutes were made from cocuswood. There are no records of how many cocuswood flutes were made under the Bay State name.

One noticeable difference between J.C. Haynes flute #1 and the later #317, as well as the Boehm & Mendler, lies in their tone hole sizes. #1 has small left hand cups and large right hand cups. The sizes of the mainline tone holes are .512” and .545”. The footjoint tone holes are larger still at .563”, and the thumb and G# tone holes are smaller at .486”. The other two flutes have single-sized tone holes in the mainline.

Initially, Boehm made his silver flutes with a continually graduated tone hole formula where the size of each hole increased slightly from the preceding one, rather than in sets of four as seen in J.C. Haynes #1. However, after six years of production, Boehm decided that the extra work in manufacturing outweighed the benefits. Flutes made after the mid-1850s were reverted to using single-sized mainline tone holes. His wood flutes did not have graduated tone holes. Haynes’s idea of making J.C. Haynes wood flute #1 with four different tone hole sizes was a bold move. Even for Louis Lot, not many of their wood flutes have graduated tone holes.

(George W. Haynes, Boston.)

The working of four sets of tone hole sizes was nothing new to the Haynes brothers. An early George W. Haynes silver flute dated around 1890 shares the same specifications as J.C. Haynes #1. It was another Boehm and Mendler copy, meticulously replicating even the distinctive tails on the trill cups. This is a seamed tube flute with soldered tone holes, made when George and Wm. S. were working together in Boston, before Wm. S. left to work for J.C. Haynes. Making the first wood flute at J.C. Haynes using the same tone hole configuration as this silver flute must have seemed an obvious choice to Wm. S. Haynes.

The sizes of the tone holes affect intonation, timbre, response, evenness, dynamics, resistance and basically every other aspect of a flute’s performance. Of course, some effects have more than one cause. After experimenting at J.C. Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes opted to make all his wood flutes with single-sized tone holes down to the footjoint. He must have reached the same conclusion as Boehm, that the benefit of varying tone hole sizes is not enough to warrant the effort. His two main competitors, Bettoney-Wurlitzer (1901-1911) and Christensen & Company (1916-1924) also made their wood flutes with the same single-sized tone hole configuration. Going out of vogue in the 1920s, American wood flutes failed to evolve past their Boehm copies into an instrument that could compete with the fashionable silver flutes. New scales, accompanied by revised tone holes sizes, would have to wait until the American wood flute revival of the late 1990s.

(Left to right: J.C. Haynes, George

Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes)

The intricate embouchure cuts of the three wood flutes show the exceptional skill of the Haynes brothers. They both chose the squarish Boehm specifications rather than the oval holes found on most contemporary French and English wood flutes. French silver flutes, however, have embouchure holes that, while not oval, are closer to a slightly elongated rectangle with curved edges. The proportion is very different than Boehm’s squarish look. For general classification of embouchure holes, please see our article The Embouchure Hole.

The wall (chimney) height of the embouchure hole on a wood flute is determined by the headjoint’s outside diameter at the embouchure hole. For our three flutes, the range is from 1.044” to 1.055”. This would yield a wall height of .181” to .187”, which would be labeled as low wall by today’s standards. To calculate wall height: subtract the inside diameter (about .681”) from the outside diameter and then divide the result by two.

A larger diameter will result in a higher wall but it may be uncomfortable for the player due to a larger radius touching the chin. A tighter curve would result in a more comfortable feel and a steeper fall in front of the blowing edge for freer blowing but would lower the front wall, producing a smaller target for the airstream. By using a raised lipplate, a flutemaker can balance the wall height and curvature independently of each other. Haynes and Louis Lot never used lipplates on their wood flutes, whereas Rudall Carte’s high-end model wood flutes are prized for their thinned headjoints with lipplates.

A radical discrepancy among the three embouchure holes is the angles of the inside front walls. They diverge from 0° (George), 5° (Wm. S.), to Boehm’s recommendation of 7° (J.C.). The walls are all relatively flat, the sides are not overcut or undercut. The Haynes brothers were capable of making all different styles of embouchure holes for wood and silver flutes, as well as piccolos and alto flutes. The choices they made for their wood flutes were deliberate and intentional, designed to achieve specific musical goals. All three flutes play well with their corresponding embouchure geometry, each carrying the spirit of producing a resonant warm tone. The feel is very different from silver flutes of the past and the present.

(George Haynes, Boston. 10.2 x

12.2 mm)

(George Haynes, New York. 10.3

x 11.9 mm)

(Wm. S. Haynes #2750. 10.7 x

13.0 mm)

Above are some of the various embouchure holes made by the Haynes brothers. An early George Haynes silver flute uses a very small, rounded shape hole. His later silver flute, dating from the same era as his wood flute here, utilizes the Boehm style squarish embouchure. An early silver Wm. S. Haynes flute, #2750 from 1914, employs a much more elongated hole. This style of embouchure hole would eventually dominate the American musical landscape for the next six decades, until Albert Cooper ushered in the modern style headjoints.

(Left to right: J.C. Haynes,

George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes)

The back connectors of a flute play a crucial role in connecting the right hand mechanism to the left hand. They operate the Bb cup, which is used for the notes Bb and high F. This type of linkage is eventually used for the pinless mechanism. The form is the same: It has a wide base touching the flute tube to regulate the key height and a top flat surface to receive the key being operated. Adjustments can be easily made on both surfaces. Flutemakers often experimented with the shapes and sizes of the back connectors to express their aesthetic view and show off their handiwork. The back connectors of our wood Haynes flutes are utilitarian, however they are well executed and express an understated elegance.

A subtle but tangible departure of the three flutes is the G# arm and cup. All three cups are punched using three separate dies. A close inspection will reveal the individual character and size of each center dap. Furthermore, the shapes of the three Y-arms are noticeably different from each other. Aside from the shape, George Haynes’s cup and arm are forged from a single piece while the other two are soldered together from two parts - a cup and an arm.

(Left to right: George Haynes

one-piece cup and arm, Wm. S. Haynes soldered cup)

By forging the cup and arm in one piece, George Haynes’s innovation allows for one less step in the manufacturing process. There are 16 cups in a flute, the time saving is not unsubstantial. The process of making a set of dies for this operation must be incredibility difficult, as no other flute companies to date have used this technique successfully.

(George Haynes tubing insert)

On the other hand, some flute companies today have adopted one of George Haynes’s modification of putting a steel (or hard rubber) insert at each end of the silver mechanism tubing. The goal is to reduce friction, thus preventing keys from binding. Furthermore, this technique can also be used to repair over-reamed mechanism tubing and minimize key noise.

(George Haynes - screws instead of pins)

One of George’s less successful improvements to the flute was the use of set screws instead of pins to combine a section of keys. This approach, essentially substituting one fastener for another, produced debatable advantages in both functionality and manufacturing efficiency. However, the Japanese company, Pearl Flute, embraces this idea and implements tiny set screws into their designs.

(Left to right: J.C. Haynes,

Wm. S. Haynes)

It is fascinating that Wm. S. Haynes made two different thumb rib configurations for the J.C. Haynes flute and the later flute #2829 from his own company. On the J.C. Haynes flute, the two posts are attached to a single curved rib. The posts of #2829 are mounted on the main rib and a small independent riblet. One clear advantage of the second design is having ample clearance for the two leaf springs under the thumb keys. Besides, it is fairly straightforward to position the small riblet with a simple jig. For the first design, fitting a curve on another curve is just a troublesome task. A simpler solution is a better one.

(George Haynes flutes from

around 1912)

But it was not the case for George. His thumb key is most ingenious, complex, and not service-friendly.

(Left to right: Reversed thumb

keys - Boehm, Wm. S. Haynes #629)

The thumb key design of George Haynes resembles some of Boehm’s designs that we now erroneously called reversed thumb Bb. According to Boehm, the logic of fingering is to close each finger in succession to obtain the next lower note. The Bb key is logically positioned to the right of the B key. However, George Haynes managed to create a design that appeared similar to Boehm’s, yet placed the Bb key to the left of the B key, as in our modern flutes.

(Left to right: J.C. Haynes,

George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes. Close up: George Haynes)

George Haynes also took his rib design to another level, adding a three-prong claw scheme. It is stylish and strong, though it requires more work and material.

(Left to right: J.C. Haynes,

George Haynes, Wm. S. Haynes)

George, a real artist and inventor, approached flute manufacturing with a unique perspective. His ideas sometimes lacked practicality and unburdened by production costs. His footjoint adjustment screw is an example of overkill. It is so beautiful and quirky. Many flute players may not even notice its artfulness as long as the low C speaks.

(George Haynes, Boston - double-sleeve thumb keys)

One last refinement that is worth mentioning is the use of the double sleeve thumb keys found on the aforementioned early George Haynes, Boston silver flute. The Briccialdi thumb key, not an original Boehm design, is ubiquitous among C flutes. Its weakness lies in the short lengths of tubing that hold two long keys, often leading to wobbling, a problem that is difficult to fix. In addition to George Haynes’s solution to this problem, two other designs have been used successfully to increase the length of the mechanism tubing: double axles and angled single axles. Neither is simple to make.

These early Haynes wood flutes laid the foundation for the Boston tradition of flutemaking. Their trial and error construction methods gradually evolved into manufacturing systems. The introduction of standard threads and caliber for steels and silver tubing remains a valid practice in modern, high-end Boston flutes. The general post height-to-tone hole distances are well balanced and were refined over time. This relationship creates a certain ergonomic feel that the player experiences, immediately recognizing it as a high-quality flute, uniquely American and particularly representative of the 20th-century Boston style.

One observation that I would like to point out is the high post height of Rudall Carte, and later Flutemakers Guild flutes. Their design afforded ample space to accommodate extra key work needed by the several competing non-Boehm systems popular in the late 19th-century London. However, the trade-off was a less efficient and comfortable environment for the player. The early French flutes of Godfroy and Louis Lot, on the other hand, have much lower post height, resulting in instruments that fit extremely well in the player’s hands. Nevertheless, this design presented manufacturing and repair challenges. The Haynes brothers’ choice of their scheme was similar to that of the later Louis Lot flutes, optimizing ergonomics with production needs.

At the start of the 20th-century Boston, there were two other top producers of wood flutes. Their flutes are very similar to the three Haynes wood flutes here.

(Bettoney-Wurlitzer flute)

The Bettoney-Wurlitzer flute is a prime example of a competitor to the Haynes flute. This flute was produced following the acquisition of Edward Wurlitzer’s Boston flutemaking concern in 1901 by Harry Bettoney (1867-1953), a skilled English flute and clarinet player. These high quality flutes were made until 1911, the year of Wurlitzer’s passing.

(Nils Christensen flute)

Nils Christensen also produced a beautiful wood flute under the Christensen & Company name. His metal flutes don’t seem to be of the same caliber as his wood flutes. Before establishing his own company, he worked for both Haynes and Bettoney. He also had a short business venture with a fellow flutemaker, John Schwelm, marketing their instruments under the name Christensen & Schwelm Company.

(A wood flute with a B-foot

costs 25% more than an equivalent silver flute.)

Wm. S. Haynes Company reintroduced their wood flute in 1998, coinciding with the appointment of Jacques Zoon, a wood flute player, to the principal flute position of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Zoon actively participated in the new venture and the model was named after him. Only about 15 flutes were made before the project was terminated in 2003. These flutes are exceptionally well made and produce the authentic sound of a proper wood flute (unlike some contemporary wood flutes, which tend to resemble the sound of a silver flute). True to tradition, the three pieces of the flute are connected by cork joints, and lipplates are not present. Some use the double-axle thumb design. The aged grenadilla wood originates from Haynes’s original stock, the age of which is unknown to anyone alive today.

In 1992, Eugenia Zukerman recorded Seven Mozart Sonatas on a wooden flute, accompanied by Anthony Newman on fortepiano. The flute featured on the album cover closely resembles a Haynes flute. Her sound is strong and very woody, full of colors. The instrumentation creates a sonic landscape markedly distinct from contemporary sounds. The playing is nothing short of fantastic.

Another remarkable player and advocate of vintage wood Haynes is Hadar Noiberg. Her website is a wealth of information.

The story of the Haynes wood flutes is short, and quickly turns into a narrative of silver French flutes. By 1921, the production of wood flutes ceased abruptly as the company pivoted its production to silver flutes, responding to market demand. There are far fewer than 2,000 flutes available for collectors and players. Some are Db or high-pitched instruments, others have reversed thumb and open G#. Time has also taken its toll, making it challenging to find an instrument in pristine condition to enjoy. The journey of searching for a vintage flute is part of the allure of building a flute collection.

by David Chu, Winter 2025, Maynard, Massachusetts

Copyright

© 2025 David Chu

For more information please email Alan Weiss at alan@vintagefluteshop.com