Vintage Flute Shop

Articles

“My Two Bonnevilles: A Collector’s Tale”

One person’s junk is

another person’s treasure.

What is the difference between junk and trash? Junk, you keep.

Thanks to junk so many beautiful flutes are still here.

(Top Bonneville #819, bottom Bonneville #926)

It was my fortune to have found these two Bonneville flutes, #819 and #926, probably made in 1884 and 1885 respectively, during a time when Auguste Adrien Bonneville (1819-1895) was operating his own shop. #819 is a silver flute, and #926 is made of silver plated Maillechort, a type I will refer to as a "tin" flute, a term I heard often from William Bennett and others. I trust that this article on Bonneville flutes will aid fellow enthusiasts in their pursuit of these exceptional instruments.

The term first-generation is most often used to describe early Louis Lot flutes given that five subsequent generations of highly successful flutemakers followed. Although Bonneville’s family-owned business has only three generations plus a short-lived spin off workshop of Bonneville Fils, first-generation Bonneville flutes are just as exceptional as those of Louis Lot.

(Logos and serial numbers, on headjoint and body)

The two flutes here are both the mature work of the father Bonneville before his retirement in 1885 at the age of 66. Their design follows that of Godfroy and first-generation Louis Lot flutes: seamed tube, serial numbers engraved on headjoint and body, one-piece rib, pinned footjoint, inline G, no adjusting screws, small three-piece back connectors, two lugs in the right hand mechanism, and small keywork. Given Bonneville’s close association with both workshops, this more traditional design choice is not surprising. Later generation Bonneville flutes do exhibit minor modifications that are in step with their contemporaries.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

These two first-generation Bonnevilles were made within a short time of each other and they represent two very different aesthetic approaches - #819 features small mainline cups and equal sized tone holes, while #926 uses the more common regular-sized cups with graduated tone holes. Both flutes share the same footjoint cup size, which is 1 mm larger than the regular-sized mainline cups, a Louis Lot innovation dating back to around 1860.

|

|

#819 |

#926 |

|

LH Tone Holes |

0.526” |

0.526” |

|

RH Tone Holes |

0.526” |

0.558” |

|

Thumb, G# |

0.500” |

0.500” |

|

Footjoint |

0.608” |

0.608” |

The mainline tone holes of #819 are all the same size. But on #926, the four right-hand tone holes are 0.8 mm larger in diameter than the left hand ones. This small difference proved significant, as the smaller tone hole design eventually became obsolete. Boehm and Rockstro championed the use of larger tone holes in the low end of the flute, aiming to create a louder, more resonant sound in that range. This is just one of the many acoustic elements that shape the instrument’s character. While increasing venting clearly boosts volume, it may come at the expense of a focused tone, which is essential for projection.

By having a silver and tin Bonneville from a similar time period, I was able to examine closely their similarities and differences. Below are some vitals at a glance.

|

|

#819 |

#926 |

|

Material |

Silver |

Tin |

|

Wall Thickness |

0.014” |

0.017” |

|

Embouchure Hole |

0.398” x 0.466” |

0.405” x 0.469” |

|

Chimney Depth |

0.190” |

0.196” |

|

Weight |

398 grams |

385 grams |

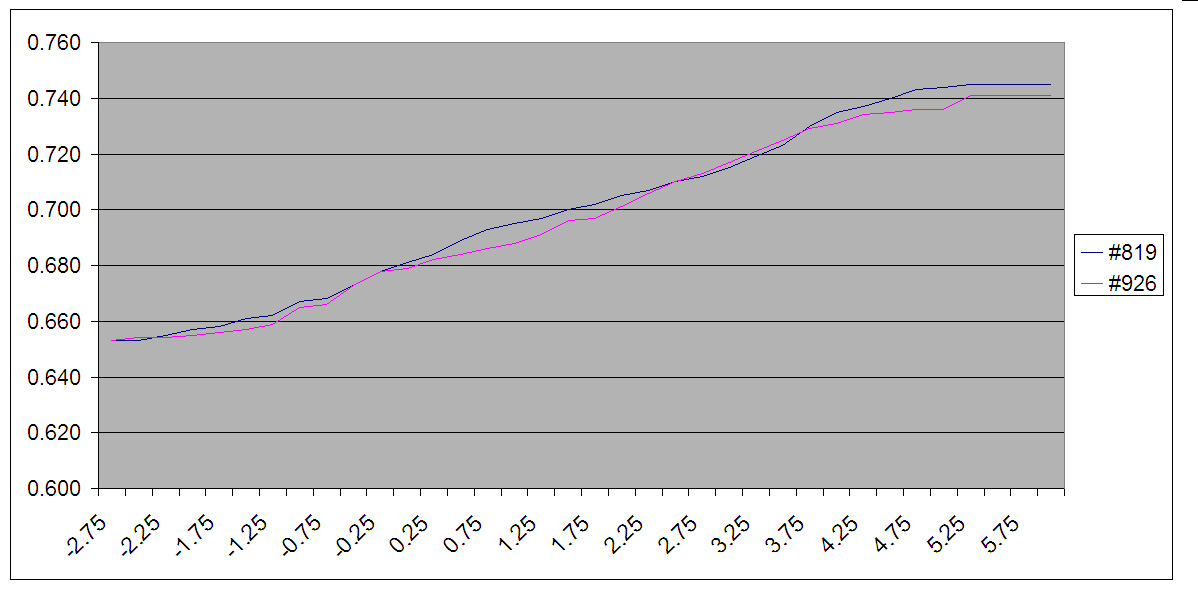

(Headjoint taper measurements)

The playing characteristics of both flutes are quite different but retain a family resemblance. There are many varieties of the French flute sound. For a tin flute, #926 plays with a warm sound not unlike a silver flute. It is more robust and less bright than what one would expect from a typical tin flute which could sound too brittle and thin. Its 385-gram mass is close to what a light silver flute would weigh. Maillechort is about 30% lighter than silver. To compensate for the reduced resistance, 19th Century Paris flutemakers often use thicker .017” to .018” body tubing. On the other hand, Bonneville made some very thin tin flutes that have incredible resonance. I used to own tin Bonneville #1015 which weights only 353 grams. These thinner tin flutes don’t survive well with the test of time unless they are well taken care of.

Silver Bonneville #819 is a very fine playing instrument. The first thing I notice is the evenness of the scale and the delicate key mechanism. Its responsiveness is remarkable, large leaps require minimal embouchure adjustment, while smaller steps flow with effortless fluidity. The tone color is particularly uniform especially in soft dynamics. It is just as easy to play legato or bouncy light staccato passages. The low notes are nearly as strong as its tin brother #926, although the approach to achieving a full sound is somewhat different. This flute reminds me of Godfroy’s metal flutes, possessing a dolce quality reminiscent of wooden flutes, yet with a more brilliant sound.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

Bonneville was careful in choosing a small embouchure with a lower chimney for #819. His sonic vision for this flute must have been core, grace and elegance. The flute’s design clearly reflects the influence of his time at Godfroy’s workshop, a place steeped in guarded tradition. Yet, while the prevailing trend, both then and now, favored a larger sound, Bonneville’s approach on this flute diverged. His contemporary and former colleague, Villette, was producing powerful instruments, pushing the boundaries of flutemaking to meet evolving musical demands. The more reserved character of #819, which echoes back to the era of Godfroy, is a tribute to Bonneville’s diverse skill set and his freedom to create instruments according to his own preferences.

#916 represents Bonneville’s more forward-looking approach. With its larger embouchure and higher chimney, it firmly belongs in the “forte flute” category. This instrument is remarkably easy to play, producing an open, joyful sound. It is a diva, eager to explore each phrase with boundless freedom, yet without any harshness. This is the recipe for a modern flute. I think all three generations of Bonneville share this philosophy, or at least strive to achieve it. My friend Andrew Sterman captures it perfectly with a driving analogy: “Playing a Louis Lot is the ultimate in nuance and elegance, but the Bonnevilles have all that while giving you another gear.” Though, in this age of self-driving cars, perhaps that metaphor might be lost on younger players.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

The craftmanship of these two flutes reveals variations in both the body and keywork, suggesting that there was more than one worker doing the same task. In order to produce an average of 100 instruments per year, Bonneville needed to employ a workforce of eight to nine people at the minimum. The workshop was about two-thirds the size of Louis Lot’s. In France at that time, workers were accustomed to working six ten-hour days per week. Bonneville’s son Alphonse Edmond Bonneville (1854-1925) would have received his training there from a young age, becoming a master flutemaker soon after the company began flute production. He took over the shop when his father retired in 1885. One of these two flutes could have passed by his workbench.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

On our two examples, the most striking contrast lies in how the ribs are beveled and pointed, and the length and symmetry of the point. It is a simple job but not an easy one to do well. Even today, this job is finished by hand with a file. Following the French tradition of his era, Auguste Bonneville used the one-piece rib design in all of his first-generation flutes. His son, Alphonse Bonneville, later transitioned to the separate trill rib design. This change occurred around the year 1889, coinciding with the production of flutes with serial numbers in the #1300s. The separate trill rib design is now common among all flutemakers due to its ease of production.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

Another small gesture is the rounding off of the end of the thumb key. Nothing fancy, just practical. The unique flavor a highly skilled worker brings to his craft is often unappreciated by consumers. The decline of guilds had paved the way for mass production. Small handmade shops like Bonneville’s were already a thing of the past even 140 years ago. The fact that the company survived until after the Great War, continuing to create beautiful flutes, is a stroke of good fortune for us.

(Top #819, bottom #926)

The footjoint cluster is a thing of beauty in old French flutes. The design is a harmonious blend of form and function, featuring the elegant dome or flat teardrop D# key. The meticulously sculpted C# spatula gracefully mirrors the curve of the teardrop before seamlessly transitioning beneath the C key. This intricate arrangement works in concert to provide the player with easy access to the low notes. The key makers who produced these two distinct footjoint clusters took time to align the touches, which are either hammered by hand or punched on a press. Each, in his own mind, knew exactly how to shape sheets of silver into working flute keys. These subtle personal touches give the flutes a lot of character.

(Left #2977, right #3140)

An intriguing D# key design has been observed on two different Bonneville flutes dating from the early 20th Century. These keys don’t appear to be aftermarket replacements, as matching the type of silver plating would have been a difficult task. The key’s symmetry and squareness suggest a departure from the traditional French curve. Interestingly, the two keys aren’t identical, possibly indicating they were hand-formed as an experiment, an attempt to introduce a fresh aesthetic. Around this time, Lebret was designing his Art Nouveau style keywork. A new century had arrived, bringing with it a new look, as the Fin de Siècle era finally gave way to the optimism of the 20th Century.

(Top #3220)

(Top Godfroy #840, bottom Godfroy #1525)

A system for the B/C shake that often found on Godfroy flutes made its way to Bonneville’s flutes. It is the use of three identical trill key touches to operate the three right hand side keys. The standard B/C (or Bb) lever, hinged on the left hand section, is eliminated. This type of keywork is significantly more complex to fabricate. The motivation behind this design choice might have been a desire for symmetry, a tribute to Godfroy, or simply a special order request.

Bonneville, both father and son, distinguished themselves from their contemporaries by their continued use of the pinned footjoint and teardrop design. This preference persisted until around 1913, corresponding to flutes with serial numbers in the mid-#3700s. At this point, a transition occurred, with flutes beginning to feature a bridged footjoint and a D# key with a more modern shape. One might speculate whether this shift was influenced by the return of Alphonse Bonneville’s son, Auguste Lucien, to the family workshop.

(Bonneville Fils logo)

Auguste Lucien Bonneville (1880-1944), the grandson of Auguste Adrien Bonneville, established his own flute company in 1908, adopting the mark BONNEVILLE FILS. For those who are unfamiliar with French, “Fils” translates to “Son” (singular) in English. Interestingly, he was, in fact, the grandson of the original Bonneville. All three generations of Bonneville have the same initials: A.B. This shared monogram appears on both Bonneville and Bonneville Fils flutes. The serial numbers of Bonneville Fils are all their own starting from #1000. Over a period of approximately five years, the company produced a total of around 500 flutes. Bonneville Fils flutes are similar to his father’s, perhaps a little bit less refined. His flutes have bridged footjoints instead of the old fashioned pinned variety. Despite the business’s failure and short lifespan, his flutes play remarkably well. From a collector’s perspective, Bonneville Fils flutes are rarities that are worth pursuing.

Most Bonneville flutes in the market place that I have come across were the Alphonse Bonneville period flutes from about serial #1000 to #5200. Alphonse’s flutes have serial numbers only on the body instead of on both the headjoint and body. That was the first modification Alphonse made when he took over his father’s workshop in 1885.

(#1157)

In 1887, Alphonse Bonneville adopted the more contemporary single “T” lug design for the right hand keys, a feature that Villette had been using on his flutes since 1877. These small modifications came incrementally at the Bonneville workshop. They are helpful for identifying the dates of their instruments.

(#1957)

One of Alphonse Bonneville’s achievements was his development of the ring key metal flutes. He applied for a patent in 1888. This ring key flute took cues from the 1832 system invented by Boehm, but using only two rings, one for venting the Bb, and the other for the F. The rings are closed using the fingers for the A and E respectively. This streamlined approach was intended to be less complex to fabricate than the full key version. It did not catch on and only a limited number were ever produced.

(#2210)

It is not inconceivable that Bonneville had an association of some degree with George Barrère since he owned #2210, made around 1898, a silver seamed tube flute with his monogram beautifully engraved on the barrel. Barrère came to America in 1905 to play with the New York Symphony. It would likely be a flute that he brought with him from Paris. The flute is now restored to tiptop condition and plays very well. The mechanism was gold plated at some point, giving the flute a truly distinguished look. It has no hallmark as Bonneville first registered his mark one year later in 1899.

(André Maquarre, possibly

holding his Bonneville flute)

André Maquarre, Barrère’s senior classmate by two years at the Paris Conservatoire, also played a Bonneville flute. He was a student of Altès. His successful career in America includes a 20-year tenure as principal flute with the Boston Symphony Orchestra starting in 1898. After that, he played with the Philadelphia orchestra (1918-21) and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (1922-29).

It is fitting that Barthold Kuijken recorded in 1999 Debussy’s Syrinx (1913) and Sonata (1915) for flute, viola and harp playing on a Bonneville flute from around 1910.

For those who are playing and collecting vintage French flutes, Bonneville is a very worthy brand and they are priced below Louis Lot’s. Bonneville's output was significant, and even with the inevitable attrition over time, there remains a large number of flutes to choose from. Some of these, from all three generations, are every bit as good as a good Louis Lot. As with vintage flutes, not all of them are in good condition and the cost of restoration could exceed the initial purchase price. Many good flutes are hidden in the rough waiting to be discovered.

Buying a “restored” flute could sometimes be worrisome because not all sellers are able or willing to disclose what has been done to the flute during restoration. A keen eye and expert knowledge can reveal telltale signs of dubious repairs, over-polishing, modified embouchure holes, mechanism flaws, grafted tenons, mismatched joints, replaced key parts, etc.

Purchasing an unrestored “attic find” flute carries its own set of risks too. Before committing to a final sale, obtain an estimate of the repair costs, if possible. An experienced repair technician should be able to accurately assess the flute’s condition. However, the playability of the flute after restoration remains uncertain until it’s in perfect playing condition. Half-baked overhauls often lead to disappointment, resulting in the owner believing the flute is inferior. In my experience, a French flute in its original, unmodified condition often lives up to the brand’s reputation.

I was lucky twice to have acquired my Bonnevilles. As the saying goes, “you have to kiss a lot of frogs to find a prince.” Before these two, I owned several later Bonneville flutes, most of which were quite impressive. One of my collecting principles, when possible, is to prioritize earlier examples of a maker’s work. As a flutemaker myself, I deeply appreciate the evolution of these artisans’ craft.

Happy Bonneville Hunting!

by David Chu, 2025, Maynard, Massachusetts

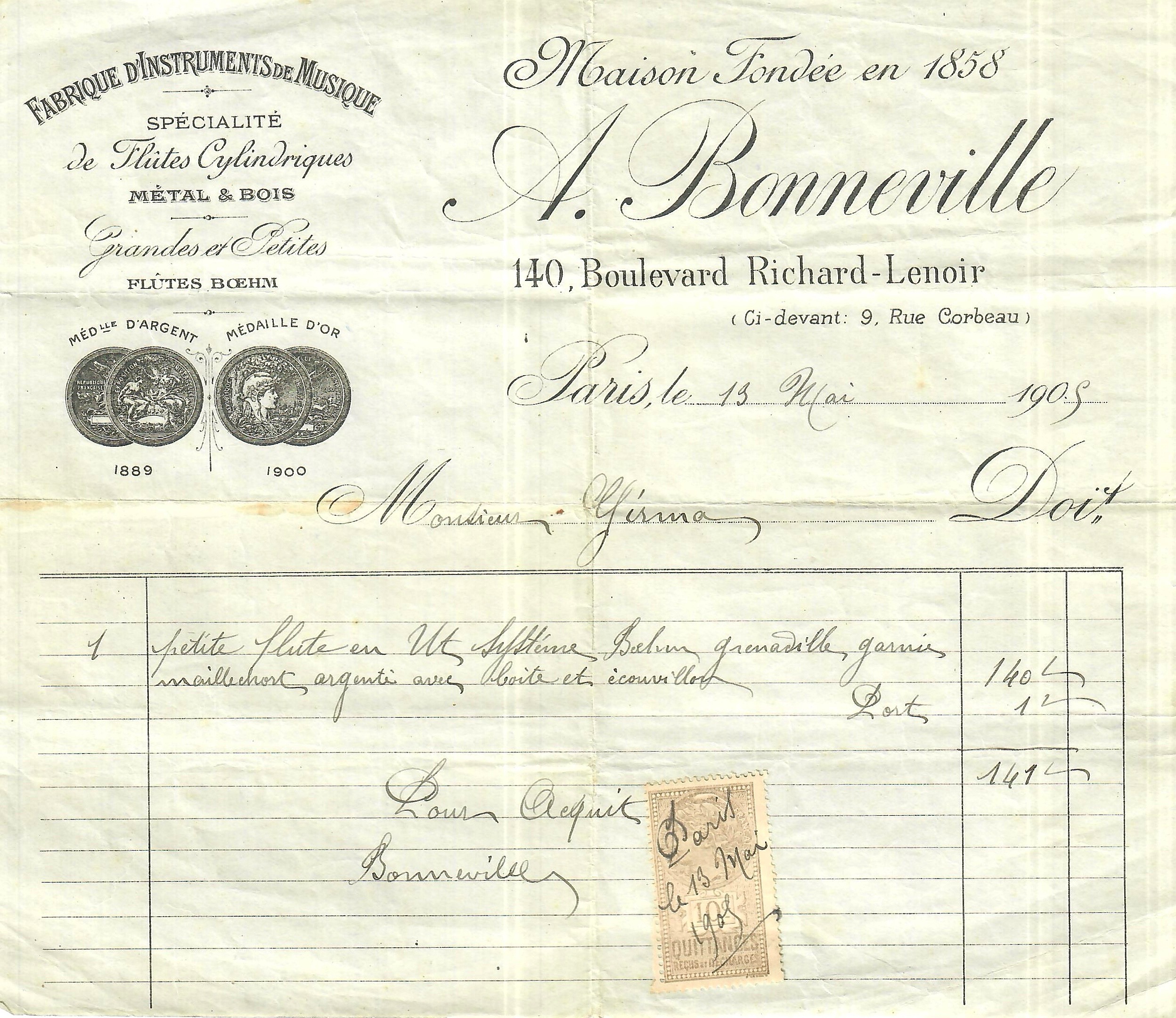

(A receipt showing the founding date of Bonneville.)

Bonneville Time Line:

1819 Auguste Adrien Bonneville

born

1854 Alphonse Edmond

Bonneville born

1858 Bonneville founded

his own business

1876 Bonneville produced his

first flute under his own name

1884 Bonneville #819

1885 Bonneville #926

Bonneville

retired

Alphonse

Edmond Bonneville became 2nd owner of the Bonneville workshop

1886 Serial number

eliminated on headjoints

Early

#1000s

1887 T-lug replaced 2

separate lugs in right hand mechanism

Early

#1100s

1888 Ring key flute

patent

1889 One-piece rib

transition to separate trill ribs

Mid-#1300s

1895 Auguste Adrien

Bonneville died

1898 George Barrère’s Bonneville #2210

1899 Bonneville

registered hallmark

1908 Auguste Lucien

Bonneville founded Bonneville Fils

1913 Pinned footjoint

gave way to bridged footjoint

End

of tear drop shape D# key

Mid-#3700s

1925 Alphonse Edmond

Bonneville died

1935 Bonneville’s family

business sold

#5500s

Currently, the Bonneville brand is dormant and under the ownership of F.Lorée Oboe.

Copyright

© 2025 David Chu

For more information please email Alan Weiss at alan@vintagefluteshop.com